Someone recently asked me: what’s the one word your friends would use to describe you? I thought about it. Then: hmm, probably intense.

I’ve been called intense for as long as I can remember. There have been multiple occasions where within 10 minutes of meeting me, someone has told me “you’re the most intense person I’ve ever met.” Is there something wrong with me? Probably. But I have grown to love my intensity—it’s what makes me me. I figure: we’re all going to die one day, so why not ride life like a fast horse? Being fully transparent, I also have no clue how to rein in my intensity, so it might be one of those things you just learn to love, like an odd birthmark you used to loathe that became your signature feature.

Related to this, I’ve been thinking a lot about obsession, relentlessness, and near-unachievable goals. What makes someone able to reach heights others view as impossible? What makes some better suited for pursuits involving a singular focus?

The answer seems to be: a capacity for intensity. Intensity is a derivative of focus. The word intense is usually used to describe someone that fixates on something with little awareness for what is going on outside of their locus of concentration. In conversation I often get called intense because I tend to zero in on a person and ask them very direct—lovingly deemed deep, but occasionally described as intrusive—questions. To me, this feels normal. I mean: isn’t that the point of conversation? Learn about each other? Explore each other’s minds? But to many, this degree of narrow focus is unfamiliar. Most people are not used to intensity, it makes them squirm.

These ideas about intensity began developing as I was toying with this idea that clarifying our thinking relies on an iterative process of trimming mental fat. Becoming maximally potent means shedding everything that isn’t necessary. Cutting the fat from your psyche—contradictions, distractions, undeclared assumptions—is how we develop clear thinking. A clear, sharp mind will cut through tasks with ease. It’s like that Michelangelo line about his process: “I chipped away at all that wasn’t David.”

I think about who I’m most drawn to, and it’s always been those that exude intensity. People with a unique ability to get consumed by something. Maybe that’s some flaw in my system—to be drawn to intense, obsessive people—or maybe I am predisposed to noticing outliers. Because pretty much every outlier is obsessive, whether we’d like to admit it or not. The obsessed do more, work harder and fall deeper into their zones of focus. Is it always healthy? Definitely not. It’s probably rarely healthy. But obsession is intoxicating. And anyone who has been obsessed knows that. Obsession pulls you in like quick sand. It immerses you. And the most startling part is that you go willingly. If you wanted to resist it, you could. But there’s that moment, that line, where you let yourself fall into it. It’s a kind of beautiful surrender—letting it take you. Scary, but seductive, and most of all: intense.

The depths you can tap into when you’re enthralled by one thing—when isolation and the object of your focus are all that exist—is mesmerizing, addictive, and certainly dangerous. But dangerous in a thrilling way, like all dark things are.

There’s that Charles Bukowski line from his poem Roll the Dice: If you’re going to try, go all the way. Otherwise, don’t even start. Most obsessive people crudely describe themselves as “all-or-nothing” types. They’ll say (read: I’ll say) that they are bad with moderation, that they need to “cut something out” if they want to cut back, which is just shorthand for “I only know how to go all the way.”

Bukowski goes on in his poem: Isolation is the gift. The rest is just a test of your endurance, of how much you really want to do it. This feels especially topical as I have begun to feel that pull of obsession to my writing. It’s like there is this constant, unrelenting tug at my psyche: get to the keyboard, get to the keyboard, you could be at the keyboard. And though I wish I could say the voice irritates me, in truth, I am on board with it. I find myself responding internally: I know! I am TRYING TO GET TO THE KEYBOARD.

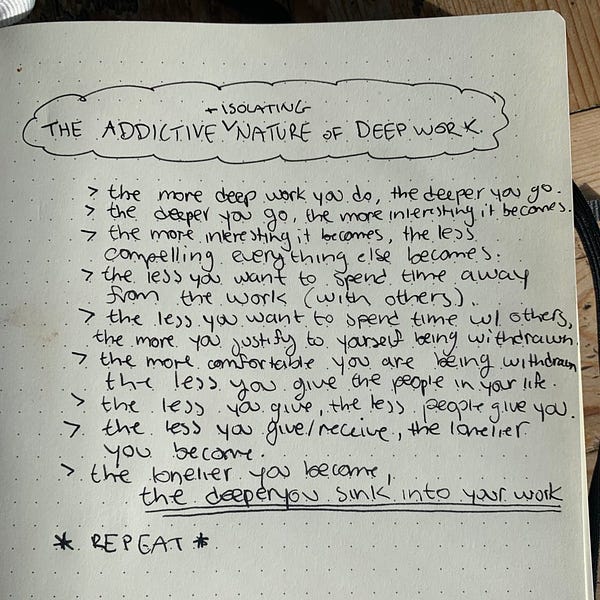

We’re on the same team—me and my obsession. I’m consenting to it, letting myself fall into the quicksand. And it’s equal parts terrifying and thrilling. Thrilling because enjoying something so much that it’s all you want to be doing is such a privilege, right? And terrifying because isolation is, well, isolating. It’s great until it’s not. There’s that point where it starts to get dark, but it’s hard to anticipate when you’re reaching that point. Giving in to your obsession means surrendering most of the commonalities you have with the world around you. The overlap between you and everyone else begins to shrink. And the portion of your identity allocated to the obsession—to the work—grows. And so you sink in deeper:

There’s a feeling when you’re nurturing a new obsession—that feeling of: I don’t want to be away from this. Ava (bookbear) captures this well in her essay moving to new york:

“I’m a year into writing (almost) every day and it still feels like a new relationship. I still wake up every morning worried that I won’t get to do it anymore. I’m still nervous, still consumed—still anxiously cutting, rearranging, extending my sentences.”

There are these subtle feelings that accompany a budding obsession, like: everything else is an obstacle, like it might run out, like there’s a new love interest in your life (the work). And being away from the work gives you that same anxious, preoccupied feeling of being away from a new love. You don’t want to lose it. You don’t want to get your heart broken.

Another notable aspect of intensity is how it commands all of you. It says: go all the way. You can’t fool an obsession by half-assing it. It demands you in whole.

There’s this bit on writing I often think of when I’m coming out of deep work. From Lovers and Writers by Lily King:

“The hardest thing about writing is getting in every day, breaking through the membrane. The second-hardest thing is getting out. Sometimes I sink down too deep and come up too fast. Afterward I feel wide open and skinless. The whole world feels moist and pliable.”

That wide open and skinless feeling is so real. When you pop out of the intensity membrane, you feel more sensitive, aware, jarred by the world around you. And it makes you want to stay in it. Protected in that warm, safe, sheltered bubble of isolation, because as Bukowski says: “Isolation is the gift.” Isolation enables the intensity. And that’s why intense people grow angsty when they can’t get back to their ‘thing’. They want to be in the membrane. Away from the surface-level triviality of the world. Everything outside of the membrane doesn’t demand their full self—it is, by definition, designed for everyone. But the intensity membrane is only accessible to the few willing to push past the barrier. Those that want to press their nose against the bubble until they break through the mundane and into the membrane. And once you’re on the other side, it is hard to compel yourself to stay out of it for too long. You’re always thinking about breaking back in.

It also becomes hard to explain what the intensity feels like to others. So it feels exhausting, uninteresting to come out of the membrane to articulate it, when you know you could be indulging in it.

This is, I think, why intense people cluster. Intensity requires a constant building of momentum. And being around other intense people lets you continue to build that momentum instead of having to constantly break it. When you’re surrounded by intense people, you don’t need to explain yourself. You can just drop into the membrane, pop back out, and both of you understand that neither of you could ever really understand what is going on in there. It’s too layered, too deep, too personal that there’s no point in discussing the contents of each other’s membranes, other than to say that it is a thrill to be in it and painful, at times, to break out of it.

Paul Graham explains why ambitious people need to be around other ambitious people (ambition being a decent analog for intensity):

“Ambitious people are rare, so if everyone is mixed together randomly, as they tend to be early in people’s lives, then the ambitious ones won’t have many ambitious peers. When you take people like this and put them together with other ambitious people, they bloom like dying plants being given water. Probably most ambitious people are starved for the sort of encouragement they would get from ambitious peers, whatever their age.”

I would encapsulate this even more simply by saying: intense people crave understanding, because they probably lacked it their whole life. Their environment always left them feeling like they were ‘too much’. No one could relate to the potency of their drive. But when intense people congregate, they finally feel understood, like they belong, encouraged by those around them. Instead of feeling inclined to conceal their intensity, they feel inclined to lean into it. And so as intensity and obsession seep deeper into the psyche and the isolation grows more inviting, being around people who get it—who have their own membranes to dive into—provides a sense of community and warmth that is elusive when one is swimming alone in the deep end of intensity.

Finding and clustering with intense people is freeing, because it lets you go from being a hungry lone wolf, to running with a pack of wolves, each with a voracity of their own. And a pack of wolves is greater than the sum of its parts, because they support and protect one another. Being around intense people lets you sink into your intensity, without needing to dim your drive.

So, while isolation can be a gift, finding intense people to exist in parallel with lets you unwrap your gifts together. And as Bukowski eludes to in the final few words of Roll the Dice—leaning into your gifts is the only good fight there is:

If you’re going to try, go all the way.

There is no other feeling like that.

You will be alone with the gods, and the nights will flame with fire.Do it, do it, do it, do it.

All the way

All the way.You will ride life straight to perfect laughter,

It is the only good fight there is.

PS — If you enjoyed this, say hi on Twitter! You also might like a related piece I wrote: obligation vs. compulsion.

Work with me 1-1: I help people discover their true desires and align their actions with their values to cultivate a life that feels true to them. This unfolds through a guided process of conversation, introspection and conscious action. Learn more about working with me here.

Unblock your ideas and express yourself freely: Creative Liberation is a 6-week virtual course, where I teach you how to go inwards, conquer your avoidance, unblock yourself, and self-express freely. Get updates about the course here.

I really love where this ended. Finding your people is very hard, but when you do it's like a wave raising a boat and sending it on its way.

this is phenomenal. how do you think intense people can build community & encourage each other?

also, two quotes I love on 'intense' people, from two very intense authors -

"[there is] some basic certainty which a noble soul has about itself, something which does not allow itself to be sought out or found or perhaps even to be lost. The noble soul has reverence for itself." - Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, #287

"And there is a Catskill eagle in some souls that can alike dive down into the blackest gorges, and soar out of them again and become invisible in the sunny spaces. And even if he for ever flies within the gorge, that gorge is in the mountains; so that even in his lowest swoop the mountain eagle is still higher than other birds upon the plain, even though they soar." - Herman Melville, Moby Dick, ch. 96