My competitiveness used to scare me. I didn’t face it for a while, because I didn’t want to believe it could make me do things I wouldn’t typically do. Eventually I had no choice but to acknowledge it was shaping my life regardless of whether I wanted to “let it” do so or not.

confronting the self

“Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.” —Carl Jung

What we fail to confront will continue to control us. This is especially true of our shadow qualities: the parts of ourselves we don’t like, that we find ugly—misaligned with the type of person we want to be. They are the wrinkles in our otherwise smooth selves. They feel shameful and confronting. We like to keep them in the unconscious, because no one likes facing their dark parts.

If it is any comfort, we all have a shadow. Every object has a shadow. No matter how wonderful we are, when the sun hits us, a black, dense silhouette trails behind us wherever we go. The same is true for personality; the aspects of the self that make us uniquely us. Even our best qualities have a dark side—just look at some of the responses in this thread:

Competitiveness is like this, too. The light side of competitiveness is that it can drive you forward, dial you in, help you perform in your highest state. The dark side: it can make you act irrationally, deal with others harshly, objectify those you compete against as nothing more than fuel to drive you forward in your own performance, and in extreme cases, it can make you hurt others for the sake of winning (see: Tonya Harding’s involvement in an attack on Nancy Kerrigan to try and secure her Olympic medal). Competitions can be ugly—they can be like war if the competitive spirit goes untamed, unconfronted.

integrating competitiveness

I want to explore the light side of competition—how to integrate competitiveness healthily into your life without sacrificing the edge it gives you. The reframe, though, is that your competitiveness only gives you an edge against yourself—which is the only person you should (and ultimately can) concern yourself with beating. The point of competing is not to beat anyone in particular, but to perform at the highest level you can. This is why competitive sports are broken up by age/level/weight class/whatever the clustering mechanism is—you’re meant to compete against the people most like you.

Competitors are just slightly augmented versions of ourselves that fall within the same band of talent as us. The people we envy the most are not the people that are 10x better than us, but the people that are 10% better than us: those performing near our level, just a few steps ahead. They are suggestions of what we could be if we just tried a little bit harder.

competitors as mirrors

“There is never anything on one side of a rivalry which, sooner or later, will not be found on the other.” — René Girard

If it is true that competitors end up being predictive mirrors for how both parties will act, then we should want everyone we compete against to perform at their best, so that they can push you to perform at your best. When someone is a few steps ahead of you in a race, you might put an extra jolt of energy into catching up and surpassing them. They raise the bar just high enough for you to clear it if you really tried. If you’re in a race and everyone decides to slack off, you won’t be running at your best, and the victory isn’t as sweet because you didn’t do anything you didn’t already know you could do.

how you play is reciprocal

“Your playing small helps nobody.”

I return to this quote whenever I feel myself contracting out of fear that someone might take my effort personally. This sounds ludicrous, but I vividly remember not wanting to step up in my middle school speech contest because I didn’t want my friends at the time to feel weird if I won (I know they wouldn’t have, btw). I immediately regretted it because speech contests were one of my favourite things. My playing small helped no one then, and it helps no one now—especially not me!

This quote also means no one else’s playing small helps you. You want everyone to play big so you can play even bigger. A high bar gives you a greater challenge to grow into—and that is a privilege.

One prominent example of one person playing “big” leading to others playing big is the 4 minute mile story. On May 4, 1954, Roger Bannister managed to run a mile in under 4 minutes—a performance barrier that for decades was thought to be impossible. In the following year, several other runners followed suit. After decades of tension between the running world and the perceived impossibility of the 4 minute mile, Bannister led a generation of runners across the boundary. He raised the bar of an entire field by applying himself to the task, by competing with himself to achieve what no one else had done.

In their book The Power of Impossible Thinking, two Wharton professors, Yoram Wind and Collin Cook write of Bannister’s achievement:

“Was there a sudden growth spurt in human evolution? Was there a genetic engineering experiment that created a new race of super runners? No. What changed was the mental model. The runners of the past had been held back by a mindset that said they could not surpass the four-minute mile. When that limit was broken, the others saw that they could do something they had previously thought impossible.”

So: one way to come to terms with competitiveness is to realize that your excellence can catalyze the collective ascent of others, not only elevating your own performance but inspiring improvement in those around you. By extension, the excellence of others raises your aim to heights you did not previously think were within reach. Or, said another way: one person playing big helps everyone play bigger. How you play is reciprocal. If everything on one side of a rivalry will eventually be found on the other, what do you want the other side to show you is possible? What can you show them is possible? How can we compete constructively?

leveraging competitiveness

Another take on competitiveness that struck me was Kobe Bryant’s answer to an interview question, asking him to describe a moment in his career where he felt like he had “arrived at greatness” (I’ll summarize it below, but feel free to watch his delivery here at the 3:05 time stamp if you’re interested):

Kobe said that the moment he felt that he “arrived at greatness” tied back to a seemingly insignificant, casual game of scrimmage between him and a suite of other NBA legends at the time. He passed the ball to his teammate who missed the shot, leading to the other team winning the game with a lay up. Kobe started flipping tables, yelling at his friend, causing a scene over their loss. His friend said, “Dude, chill, it’s just a game.” Kobe returned the locker room, fuming.

Still thinking about this game days later, unable to let the loss go, he realized: hey, maybe this isn’t just a game for me… maybe I am built a little different. What he was describing as “arriving at greatness” was his moment of confronting his shadow—the moment he realized his intense competitiveness was baked into who he was. He could reject his competitiveness, becoming a blind victim to it, or he could leverage it to help everyone play bigger. And we all know which path he chose.

This had me reflecting on my relationship with my own competitiveness. A specific moment that came to mind when I heard this story. I was in high school and my Dad had just come home from speaking with my Chemistry teacher at parent and teacher interviews. He told me that she asked him where my drive to perform in school came from. To my dismay at the time, he told my teacher that it came from my competitiveness—that “I always wanted to be the best at whatever I did.” I remember being taken aback by the observation, and in complete denial of it. I was furious with him. I remember thinking: He thinks I only do well because I am competitive? That’s ridiculous! Everything I do comes from me and is for me! Of course, I didn’t realize that both could be true simultaneously. You can be competitive and intrinsically motivated. Your competitiveness can fuel your intrinsic motivation by internalizing what excellence looks like in others.

It took some maturity before I realized that my competitiveness was, in fact, a force that drove much of my performance growing up. As with many things, sometimes the people around us (especially our parents), see things in us before we can see them in ourselves. This “Kobe” moment of realizing: maybe I am built a little different, showed me that my tendency to approach things with an intensity and voracity that some might view as “extra”, but to me is just me might just be okay. Helpful even. I realized that when I own my competitiveness instead of letting it own me, I can harness it to expand my own (and others’) view on what is possible, elevating myself and those around me. Just like Bannister did with the 4 minute mile, and Kobe did with basketball.

competing with kindness

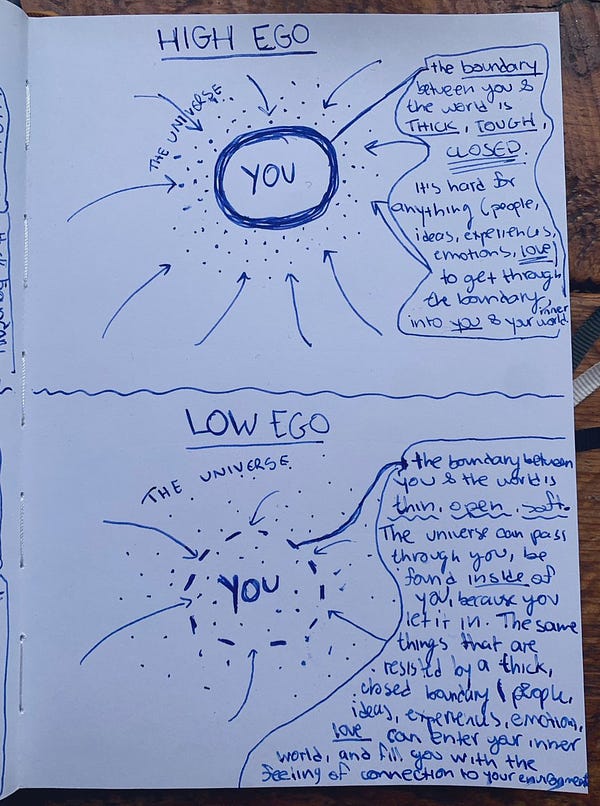

Pulling on a thread from my humility vs. hubris piece, there is a way to both be low ego, and to compete fiercely. The thrust of being low ego is to view the world around you and those in it as an extension of you. It is remembering that anything that bothers you in others is something that also exists in yourself. It lets you treat others with compassion, patience, kindness.

On some very real level, the way you treat others is how you treat yourself. If you let yourself become resentful, spiteful, angry—you might think you are directing that energy towards someone else, but you are only filling yourself up with it.

The same goes for how you compete: since your competitors are pseudo-versions of you, you want to compete against them the same way you would compete with yourself—with respect, humility, compassion, grace. You wouldn’t want to beat or hurt yourself, hence: you don’t want to hurt those you compete with. When we see competitors congratulating each other and say “now that’s a great competitor”, what we are observing is one competitor treating another the way they would want to be treated. When we treat others well, we treat ourselves well. We compete from abundance. We understand that the success of others only pushes us to greater heights ourselves.

I am always inspired by a display of healthy rivalry—like J. Cole and Kendrick going head to head in Black Friday. What I find moving is the reverence they have for each other in their lyrics and in their attitudes towards each other. They push each other to be better—you can hear it in their voices. The battle makes them hungry—not necessarily to “beat” the other, but to be the best they can be, to win against themselves, to do better than they’ve ever done before. This is the purpose of competition: to put you in an environment that pushes you to be better than you would be performing alone.

compete with yourself

Comparing ourselves to someone else is hard to do accurately. We all have unique gifts, talents, work ethic. The only person you can compete in full confidence against is yourself: only you know what you did yesterday, what you are capable of, what you are really doing with your time. Competing against anyone else would be to compete against their results—which, while helpful, is not a holistic metric. Competing against yourself lets you factor in your process, effort, day to day activities, how you treat yourself through it all. You only get a full window into your own existence (which can still be hard to examine earnestly, but at least you have all the data to do so).

compete from abundance

Use others as fuel to continue enriching the competition you have with yourself. If you feel like you aren’t a sufficient rival, look outside of yourself as a reminder that others are grinding for the same things as you. But the only person who can ultimately capture those things for yourself is you. If they do worse, you don’t do better. That’s not how life works—the only thing that can drive you forward is your own self-activation.

The world is so big that the abundance each individual can capture is effectively infinite—just look at any of the people who have done the “most” in the material world (Elon, Bill Gates, etc). People complain that they have too much, which is another way of saying that they got too close to infinity.

Aiming for greatness is realizing that your success won’t come from taking the success of another away, but from organically generating greatness within yourself. No one else’s success takes away from yours, only you can do that by putting a thought like that in your own head. Do the opposite: view the success of others as encouragement, as a new bar to jump over, as evidence we are all more capable than we think. Recognize the infinite potential available to everyone, and compete from abundance (them winning motivates me to win bigger) instead of scarcity (them winning means I’m losing). When you compete from abundance by understanding your success doesn’t take away from anyone else’s—it only adds—and vice versa, you create more abundance for everyone by performing well.

confronting competitiveness

I thought being competitive was an ugly quality, one to be ashamed of—I didn’t want to be doing things out of spite or fear of losing. I wanted to be doing them for me. I now realize that I was, and still am: I like to push myself to the highest level I can. And looking at the performance of others (competing) is merely a way to enhance that internal drive.

In gymnastics, I always wanted to be training with the best athletes. The benefits of training with those better than me seemed obvious: greater motivation, higher aim, the belief I could do harder skills because those around me could do harder skills. The same holds for real life. You always want to be in the highest performing group you can be in. It’s the “you’re the average of the five people you surround yourself with most” quote over and over again. The more excellence you expose yourself to, the more excellence you can capture yourself.

Competitiveness is nothing to be ashamed of—it’s powerful. They key is to remember that you are competing with yourself to outperform the person you were yesterday. If you do that every day, no one will catch you. You will elevate yourself so consistently that finding others who compel you to raise your aim will become increasingly difficult. The good news is: you can always find a worthwhile rival in yourself. When we focus on beating ourselves, we accelerate our own becoming. And what could feel more victorious than that?

Do you resonate with what I write about? Maybe we should work together: If you resonate with the ideas I write about and want to cultivate a life you genuinely enjoy living, where you align your actions with your values, move towards the changes you know you want to make, and consciously harvest self-knowledge in the process, send an email to isabel@mindmine.school or to isabel@mindmine.school or DM me on Twitter to explore what working together 1-1 would look like.

PS—Most of my thoughts spill onto Twitter before they make it here. If you liked this piece, you might also enjoy my piece you vs. you or intensity. Thanks for being here :)

Don’t compete with anyone. Let everyone compete with you. When you compete with others, you're living up to their standards, not your own. Don’t compete, perform at your highest standard and do your best.

A great post, as always.

In my writing work I'm mostly trying to approach competitiveness as a vehicle towards self-esteem; being able to adapt the mindset of a competitor (and having the experience of working towards a goal) feels like a victory I can earn "for me."

I guess where I'm stumbling is that thought that I could always bes pending my time better, and the idea that "competing against the person I was yesterday" never seems satisfying, because I'm not giving myself the credit actually doing valid work in that time.

I feel like this piece comes from the position of high self-esteem (not sure if you equate that with your "high ego/low ego" definitions or not); there doesn't seem to be much questioning of the motivations, the validity of the motivations, or a negative perception of self along that journey. I realize you've only volunteered a small side of yourself in the anecdotes here, but would love for you to write on that if you have it in you.